Story and photos by Judy Benson

Carl Jorgensen, consultant to the Plant Based Foods Association and the Plant Based Foods Institute, talks about the potential of kelp in the plant-based food industry during the 8th Annual Connecticut Seaweed Stakeholders Meeting. Plant-based alternatives to meat, milk and other foods derived from animal products are the fastest growing sector of the food industry, as more consumers identify as “flexitarians” who want to eat in a healthier, more environmentally friendly way.

Carl Jorgensen, consultant to the Plant Based Foods Association and the Plant Based Foods Institute, talks about the potential of kelp in the plant-based food industry during the 8th Annual Connecticut Seaweed Stakeholders Meeting. Plant-based alternatives to meat, milk and other foods derived from animal products are the fastest growing sector of the food industry, as more consumers identify as “flexitarians” who want to eat in a healthier, more environmentally friendly way.

That means the time is ripe for Long Island Sound kelp growers to actively seek out food product companies to purchase their harvest. So said Carl Jorgensen, consultant for the Plant Based Foods Association and its sister nonprofit, the Plant Based Foods Institute, to an audience of kelp growers and regulators at the 8th Annual Connecticut Seaweed Stakeholders Workshop. Carl Jorgensen, consultant to the Plant Based Foods Association and the Plant Based Foods Institute, talks about the potential of kelp in the plant-based food industry during the 8th Annual Connecticut Seaweed Stakeholders Meeting.

“I believe the plant-based food industry represents a potential market for the seaweed industry,” said Jorgensen, speaking at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station in New Haven on Sept. 27. “It’s really a matter of getting this industry familiar with seaweed.”

He recommended growers attend plant-based food expos and offer seaweed samples to exhibitors to use as an ingredient in processed foods and as a standalone product.

“You could very well come away with some customers,” he said, “but you have to get out there and get yourself known.”

The biggest challenge for plant-based food companies, he said, is creating products that with an appealing “umami” taste that mimics the savor of meat products. Seaweed, he said, has a rich, complex flavor that could be a key ingredient in achieving that goal.

“As a part-time vegan and a full-time vegetarian,” he said, “I’d eat a kelp burger.”

The workshop, hosted by Connecticut Sea Grant, brought together growers and regulators to share updates and challenges the nascent industry is facing, and share ideas about how to unleash its potential. After Jorgensen’s talk, the meeting moved to another location in New Haven, the nursery run by GreenWave, a nonprofit working to advance the seaweed industry. The nursery produces the seeded string needed to grow kelp.

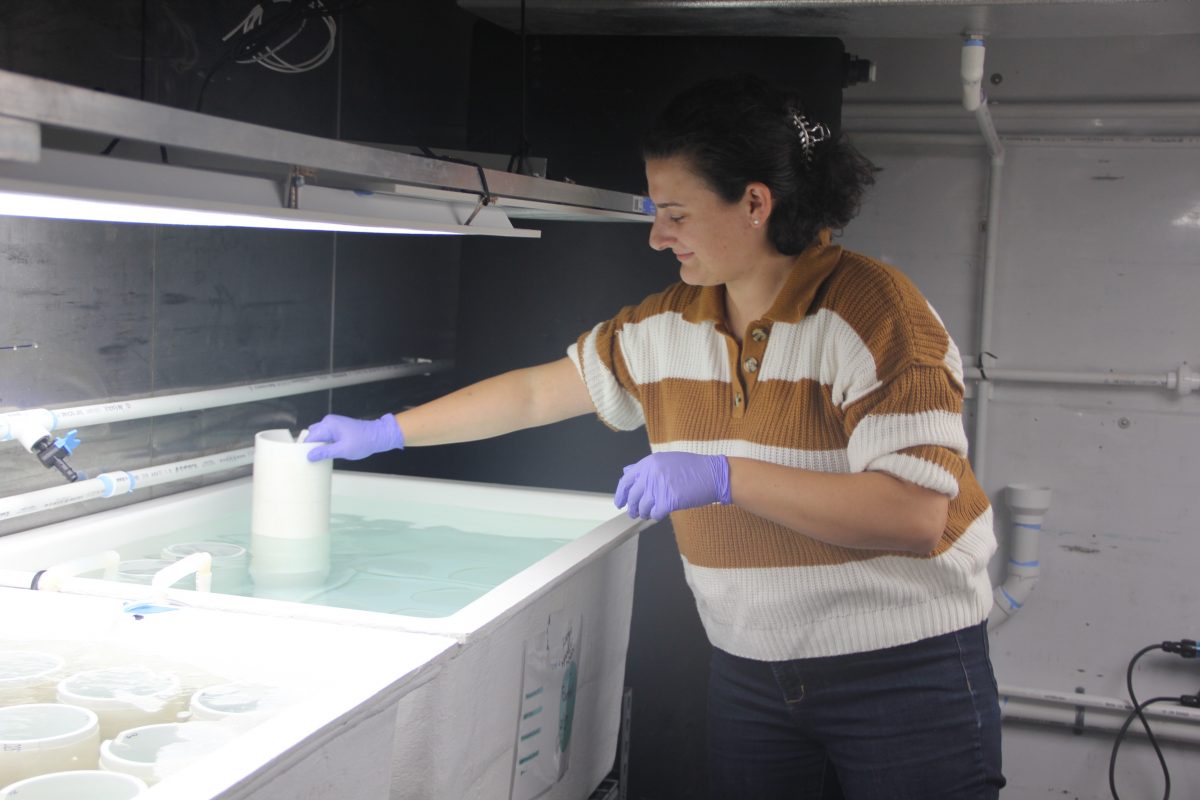

Toby Sheppard Bloch, director of infrastructure at GreenWave, led a tour of the nursery, which was expanded and renovated in 2021 to be able to produce 74,000 feet of seeded string per growing season, double its previous capacity. The seeded string is then sold to farmers for planting in the Sound for $200 per spool.

“Everything in this system is affordable and readily available,” Sheppard Bloch said.

He took the group from the large tanks where seawater is sterilized before being used as the growing medium. An adjacent room holds eight 65-gallon seawater-filled tubs packed with PVC pipe spools. The spools are wound with string saturated with a solution containing the kelp reproductive material that develops into seed.

In another room, Michelle Stephens, hatchery manager, and Maggie Aydlett, kelp seed production manager, used large artist brushes to paint the reproductive material onto the spools of string.

Meeting organizer Anoushka Concepcion, Connecticut Sea Grant associate extension educator, said the annual stakeholders gathering provides important opportunities for growers and regulators to network, share ideas and learn about possible new markets.

“Connecticut Sea Grant, in partnership with the Connecticut Department of Agriculture Bureau of Aquaculture, has been organizing this workshop since 2015,” she said. “It is the one time of year all the regulatory agencies, industry and other supporting sectors convene to tackle challenges preventing the industry from expanding. It is wonderful to see the progress being made through collaboration.”