Connecticut is bear country. It may sound strange, but western Connecticut is home to a growing population of American black bears. While bears may at times look out of place in the fourth most densely populated state, black bears living around humans is becoming more and more common not only in Connecticut, but across North America. This new reality has instigated new research to understand how bears respond to development, and may require a shift in human perspective to coexist with bears.

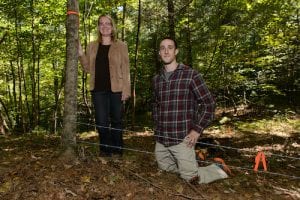

Tracy Rittenhouse, assistant professor in the Department of Natural Resources and the Environment, focuses her research on how wildlife responds when habitat conditions change. Rittenhouse is interested in key questions about how wildlife interacts in their habitat and what happens as Connecticut becomes a more exurban landscape, defined as the area beyond urban and suburban development, but not rural.

Rittenhouse wants to see from a management perspective what species are overabundant and what are in decline in exurban landscapes. She is interested in looking at the elements of what is called “home” from the perspective of a given species.

In Connecticut, 70 percent of the forests are 60 to 100 years old. The wildlife species that live here are changing as the forest ages. Rittenhouse notes that mature forest is a perfect habitat for bears and other medium-sized mammals as well as small amphibians.

Black bears like this mature forest because they eat the acorns that drop from old oak trees. Forests are also a preferred environment for humans. Exurban landscapes that are a mixture of forest and city are becoming the fastest-growing type of development across the country. The mixture of the city on one hand and the natural environment on the other is positive for humans, but it is not yet clear if wild animals benefit from this mixture.

Exurban landscapes are ideal places for species that are omnivores and species that are able to avoid people by becoming more active at night. Species that shift their behavior to fit in with variations in their environment survive well in exurban locations.

Rittenhouse collaborates with the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection’s (DEEP) Wildlife Division on real life wildlife issues. “Working with DEEP is my way of making sure I am asking research questions that are applicable to real world situations,” she said. “I often try to identify actions that wildlife management professionals or urban planners can take that will allow a species to live in an area. The action is often simple, often a slight change, but we hope that a small change may keep a species from declining or becoming overabundant.”

“We studied black bears by collecting hair samples. Collecting black bear hair is not as difficult as it sounds, as bears will use their nose to find a new scent even if they need to cross a strand of barbed wire that snags a few hairs. The hair contains DNA and therefore the information that we used to identify individuals. For two summers we gathered information on which bear visited each of the hair corrals every week. In total we collected 935 black bear hair samples,” Tracy says.

As Connecticut residents revel in the open spaces of exurban lifestyles, Tracy Rittenhouse and her students keep watchful, caring eyes on the effects of human behavior on wild animals that have no voice. Home may be where the heart is or where one hangs one’s hat, but for the wild critters of Connecticut, home may be a precarious place as they adapt to change.

Article by Nancy Weiss and Tracy Rittenhouse