By JUDY BENSON

Haddam – As the state gets wetter, Connecticut cities and towns have little choice but to take better control of the water that flows over streets, parking lots and fields from rainfall and snowmelt.

“There are two drivers related to stormwater,” said David Dickson, faculty member of the UConn Center for Land Use Education and Research (CLEAR). “One is climate change. New England is seeing more rain and more intense rainfall events. The other is the MS4 general permit, which became effective in 2017.”

Dickson, speaking at a March 22 symposium sponsored by the UConn Climate Adaptation Academy, explained that MS4 — the shorthand term for the new state regulation for how municipal stormwater is managed — now requires cities and towns to reduce nonporous pavement on streets, sidewalks and parking lots. It also requires they establish “low impact development” practices as the standard for new construction. The state regulation is the result of a federal mandate under provisions of the Clean Water Act requiring gradually stricter rules to curb pollution.

“Towns have to enter into a retrofit program to reduce impervious surface areas by two percent by 2022,” Dickson said. “LID now has to be the standard for development. You can’t just say it’s too costly. This is going to change how we think about site development in this state.”

The third workshop in a series on the impacts of changing weather patterns on local land-use practices, the symposium drew about 50 municipal officials from around the state. It was presented at the Middlesex County Extension Center by the Climate Adaptation Academy, a partnership of CT Sea Grant, CLEAR and the UConn College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources. The Rockfall Foundation co-sponsored the event.

Overall, the purpose of the session was to educate local officials about “what works and what to watch out for to ensure success” when it comes to implementing low impact development, said Tony Marino, executive director of the Rockfall Foundation.

Dickson, the first of the four presenters, explained that with increasing amounts and intensity of precipitation, the impacts of unmanaged stormwater carrying road and agricultural pollutants into the environment are increasing.

“Stormwater is the top source of water pollution into Long Island Sound,” he said.

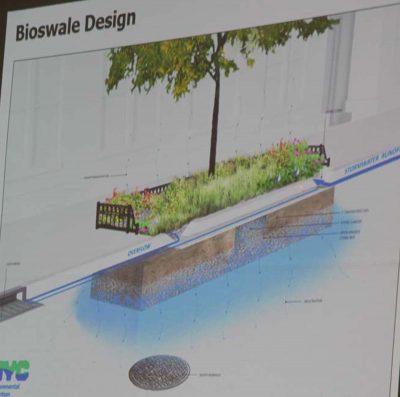

In the 1990s, low-impact development techniques emerged including “green roofs” covered with planted beds to absorb rainfall, grass swales to replace curbs and gutters, rain gardens and bio-retention areas with trees and shrubs situated to absorb runoff, and permeable pavement that allows water to infiltrate into the soil. That allows the soil to capture pollutants and groundwater to be recharged.

Since then, LID designs have been used at several sites on UConn’s main campus and in the Jordan Cove housing development in Waterford, among other locations around the state. While at least one-third of towns in Connecticut have adopted LID techniques at various levels, Dickson said, the new regulation means all towns will have to commit to making them the standard practice because it’s an economical and effective way to comply with the requirement to curtail stormwater runoff.

“Towns will have to start thinking about where impervious cover drains directly into their stormwater system, and enter into retrofit programs to reduce impervious areas,” he said.

Michael Dietz, water resources educator with CLEAR, said that more than 20 years after they were built, the LID features in the Jordan Cove development are still working. Research shows significantly less runoff coming from the portion of the development with LID compared to the control section built with traditional design features, he said. The LID structures continued to function even when the homeowners failed to maintain the areas correctly, he noted.

“The take-home message is that LID mostly still works, in spite of what people do,” he said.

At the main UConn campus, Dietz said, LID has “become part of the fabric of the design” for all new construction since it was first used in the early 2000s. But over those years, there have been mistakes and lessons learned, he added. In one case, curbs were installed where they weren’t supposed to be so runoff ended up being directed away from a bio-retention area. In another case, the bio-retention area was poorly located on the way students took to a dining hall, creating a compacted path that reduced its effectiveness.

“We failed to factor in people,” Dietz said.

The area, he said, was redesigned with a footpath through the middle that still allowed for runoff capture.

In another example, a parking lot next to the field house covered with permeable concrete “totally failed” last year and was allowing for “zero infiltration.” The concrete was not mixed and handled properly, he said, and curing time was insufficient, among other problems. It has been replaced with pre-cast pervious concrete blocks. Other challenges include the need for regular cleaning of pervious pavement to unclog porous spaces.

“You neglect it, it costs you down the road,” Dietz said.

Giovanni Zinn, city engineer for New Haven, said the dozens of bio-retention areas, rain gardens, swales and pervious pavement areas installed around the city do require more planning and attention.

“But if you simplify your designs, the construction will be less costly and they’ll be easier to maintain,” he said. Overall, he added, maintenance costs are less costly than for traditional infrastructure.

He advised choosing low-maintenance plantings and involving local residents and community groups in the projects. Looking ahead, New Haven is planning to build 200 more planted swales to capture runoff in the downtown area and another 75 in other parts of town.

“The bio-swales are the first step in dealing with our flash flooding issues in the downtown,” he said.

David Sousa, the final speaker, is a senior planner and landscape architect with CDM Smith, which has its headquarters in Boston and an office in East Hartford. Instead of talking about development practices to minimize runoff, Sousa focused on “how to avoid it altogether.”

He advocated for compact urban redevelopment over “big box” stores with large parking lots. Not only does this give residents stores and restaurants they can get to on foot, by bicycle or mass transportation, “it also saves acres of green fields.”

“It’s being done in our communities,” he said, citing examples in Mansfield, Stamford and Middletown. “But it’s not being done enough.”

Redevelopment of urban areas, he said, creates communities that use fewer resources, which in turn is better for the environment.

“The carbon footprint of people in cities is so much less than those with suburban lifestyles,” he said. “With less vehicle miles traveled, there is less need for impervious parking surfaces, less stormwater flooding and less emissions. We need to think about ways to avoid using LID in the first place.”

Judy Benson is the communications coordinator at Connecticut Sea Grant. She can be reached at:judy.benson@uconn.edu