By: Sheila Foran & David Bauman for UConn Today 4/10/13

Connecticut residents generally have dependable access to food, but the picture is not all rosy.

A recent U.S. Household Food Security study showed that about one in seven households in the state reported not having enough money to buy food they needed in 2011. And agriculture officials say that between 2008 and 2010, nearly 13 percent of Connecticut’s residents lived in “food insecure” households, while 38 percent of those residents lived in “households with very low food security.”

A new study by the University of Connecticut’s Zwick Center for Food and Resource Policy and Department of Cooperative Extension, 2012 Community Food Security in Connecticut: An Evaluation and Ranking of 169 Towns, evaluates the state’s capacity to address food security challenges and provides a guide for policy makers on how to get food resources to the state’s residents most at risk.

The UConn study focuses on a town-level assessment of factors affecting the state’s “food security,” a socioeconomic term that defines easy access to safe and healthy food.

“Although it is extremely difficult to pinpoint where food insecure households are located, one can look at certain variables such as location of food retailers, bus routes, and participation in public food assistance programs to draw comparisons on a town-by-town basis,” says Jiff Martin, a sustainable food system associate with UConn’s Cooperative Extension System and co-author of the study.

Conducted by UConn researchers in cooperation with the Connecticut Food Policy Council, the study updates a previous UConn report in 2005 that was the first to examine community food security in the state. After seven years, the current report offers a new assessment of community food security that should be of interest to town planners, and civic, environmental, and public health authorities seeking to reduce disparities in access to healthy food across the state, say the study authors.

John D. Frassinelli, chair of the Connecticut Food Policy Council, agrees: “This update to the 2005 study will be very useful for groups working on the ground, as they assess their progress and make decisions regarding resource allocations to have the most impact.”

To define “community,” the study adopted the boundaries of Connecticut’s 169 towns and created three rankings to examine each community’s food system: population at-risk for food security; retail food proximity; and public food assistance programs. Each ranking combines several variables into one discrete measure that is used to assess each town’s capacity to provide its residents access to healthy food.

For the first ranking – population at-risk – the measure includes a town’s population mix using poverty and unemployment rates, and socioeconomic characteristics such as income, vehicle ownership, educational attainment, and number of children per household, to determine the likelihood that a town’s residents might be food insecure.

The food retail measure considers each town’s proximity to food retail stores and the variety of food cost options these establishments make available to a town’s population. Given residents’ ability to shop for food in neighboring towns, this measure considered not just the closest food retailers, but all retail options within a 10-minute drive from a town’s population center.

The food assistance ranking measured how well a town’s residents are being served through public food assistance programs, and whether public bus transportation is available to provide people access to food resources.

To interpret the rankings, if a town is identified with a large population at-risk for food insecurity, for example, then it can examine how well it is providing for its residents through both access to food retailers and whether residents are being served through public food assistance services and public bus transportation.

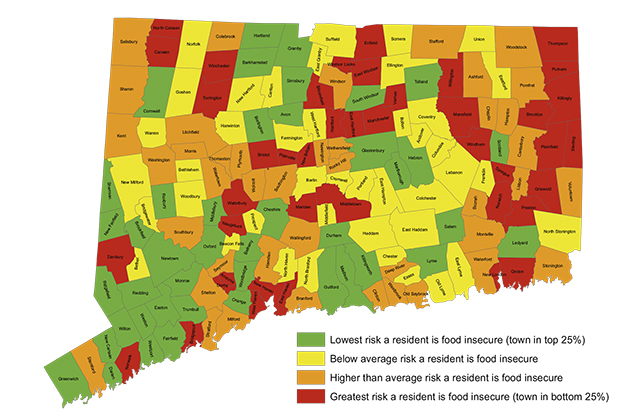

The study maps all of Connecticut’s 169 towns to provide a visual picture of each town’s performance. The maps will be useful for comparing needs and performance between towns, notes Adam Rabinowitz, senior researcher with UConn’s Zwick Center for Food and Resource Policy and co-author of the study.

“On all of the maps, there are some very apparent clusters of similar rankings throughout the state, but the maps also provide an easy identification of where neighboring towns rank starkly different,” says Rabinowitz. “This is a great opportunity to start questioning why those differences exist in these adjacent areas.”

Given that Connecticut has towns with vastly different sizes, the study also created five categories of town size – based on population – and ranked towns within each category to compare towns of a similar size. Maps of the rankings based on town size categories are also available on the study’s website.

The study should be of interest to town leaders, anti-hunger advocates, and community groups seeking to improve access to healthy food in Connecticut, notes Rabinowitz, adding that growing public interest in safe and healthy food is fertile ground for policy makers to focus attention on the goals of community food security.

“We hope,” Rabinowitz says, “that these results will be used to stimulate town-level discussion, and may even help prioritize further analysis and commitment to strategies that will strengthen community food security in Connecticut.”