Protecting People and Animals from Tick-Borne Diseases

Author: Sara Tomis, UConn Extension and Maureen Sims, Zeinab Helal, and Holly McGinnis, Connecticut Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory

onehealth@uconn.edu

Reviewer: Dr. Sandy Bushmich, UConn

Publication EXT151 | August 2025

Introduction

Ticks and insect vectors can host a multitude of disease-causing agents that can harm the health of humans and animals. This fact sheet integrates a One Health approach to understanding and responding to vector-based health risks, and is designed for individuals and groups interested in learning how to protect themselves and their animals from tick-borne diseases.

Tick Characteristics and Behavior

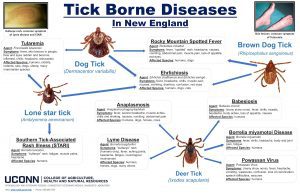

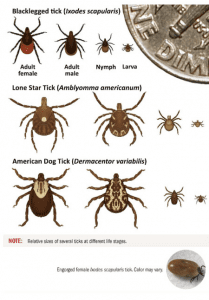

If you call Connecticut home, you likely have heard about the risks that ticks present. There are many species of ticks that can transmit diseases (Figures 1 & 2). The ticks most commonly found in Connecticut are:

- Deer tick (aka Blacklegged tick): (Ixodes scapularis)

- Dog tick (Dermacentor variabilis)

- Lonestar tick (Amblyomma americanum)

- Brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus)

- Asian Longhorned tick (Figure 3) (Haemaphysalis longicornis) new, invasive species found in coastal areas of Connecticut

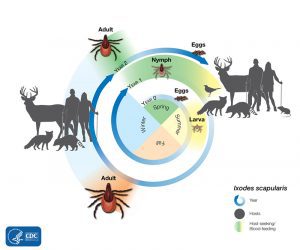

Ticks have four life stages-egg, larval, nymphal, and adult (male or female) (Figure 4). Ticks can be active yearround, whenever temperatures are over ~50°F. However the life stage will vary depending on the time of year. Deer tick (Figure 4), adults are active in the spring and late fall months, while the nymphal stage is active late spring/summer. The larval stage is active during late summer. Most tick-borne diseases can be transmitted during the nymph and adult stages.

With the exception of the Lonestar species, ticks exhibit ‘questing’ behavior when searching for a host, where they cling to the end of a blade of grass or other vegetation, and extend their legs waiting for a host (person or animal) to pass by.

Lonestar ticks are more aggressive and will actively search for a host. Once attached to the host, the tick will feed for several days before detaching. This step is necessary for the tick to complete this stage in its life cycle and is also when, if infected, the tick may transmit diseases to its host. For example, Lyme disease infections typically require at least 24 hours of tick attachment, whereas Powassan virus has been shown to be transmitted in as little as 15 minutes.

Tick Diseases

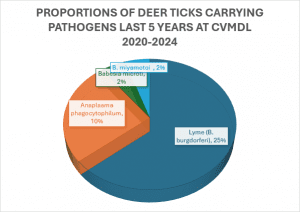

The Connecticut Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory (CVMDL) at the University of Connecticut is one of the laboratories involved in testing tick-borne pathogens. Over the past five years, the lab has received approximately 2,000 tick submissions for analysis. These submissions have included a variety of tick species, such as Ixodes scapularis (deer tick), Dermacentor variabilis (American dog tick), Amblyomma americanum (Lone Star tick), Haemaphysalis longicornis (Asian longhorned tick), Rhipicephalus sanguineus (brown dog tick), and Amblyomma maculatum (Gulf Coast tick).

Among the pathogens detected, the most commonly identified was Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium responsible for causing Lyme disease, and is primarily associated with the deer tick. Figure 5 shows a summary of pathogen detections in deer ticks from 2020-2024.

Summary of Common Tick-Borne Diseases, Associated Tick Vectors, and Symptoms

| Disease/Condition | Causative Agent | Associated Tick | Symptoms |

| Lyme Disease | Borrelia burgdorferi (bacteria) | Deer Tick | Bullseye rash (humans only), fever, aching joints, headache, fatigue, neurological involvement |

| Anaplasmosis | Anaplasma phagocytophilum (bacteria) | Deer Tick | Fever, severe headache, muscle aches, chills and shaking, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain |

| Babesiosis (human only) | Babesia microti (parasite) | Deer Tick | (Many show none ) fever, chills, sweats, headache, body aches, loss of appetite, nausea |

| Borrelia miyamotoi disease | Borrelia miyamotoi (bacteria) | Deer Tick | Fever, chills, headache, body and joint pain, fatigue |

| Powassan | Powassan virus (virus) | Deer Tick | (Many show none), fever, headache, vomiting, weakness, confusion, loss of coordination, speech difficulties, seizures |

| Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever | Rickettsia rickettsii (bacteria) | Dog tick

Brown dog tick |

Fever, ‘spotted’ rash, headache, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, muscle pain, lack of appetite, red eyes |

| Ehrlichiosis | Numerous Ehrlichia species (bacteria) | Dog tick

Lonestar tick Brown dog tick |

Fever, headache, chills, muscle pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, confusion, red eyes |

| Tularemia | Francisella tularensis (bacteria) | Lonestar tick | Fever, skin lesions in people, face and eyes redden and become inflamed, chills, headache, exhaustion |

| Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness (STARI) | Borrelia lonestari (bacteria) | Lonestar tick | Bullseye rash, fatigue, muscle pains, headache |

| Alpha-gal syndrome/ red meat allergy | Although this is not a disease, the alpha-gal syndrome is important to note | Lonestar tick (other species of ticks might be involved, as well) | Allergic reaction

*Note: the tick cannot be tested for this syndrome-please consult your healthcare provider with any concerns. |

Prevention Recommendations: Human Health

The best way to prevent tick bites is to avoid areas where ticks are active but, of course, this isn’t always possible because people enjoy spending time outside.

Things that you can do to lower your risk of a tick bite:

- Wear a long sleeve shirt and long pants, and tuck pants into socks while engaging in activities outdoors, such as hiking and gardening.

- Treat the outside of your clothes with an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-approved tick repellant.

- Once back at home, remove clothing and immediately place in the washing machine and wash with hot water. Drying clothes at high temperature (even without previous washing) is also very effective in killing ticks. Ticks can hitch a ride on your clothing and bite you later.

- Promptly shower and perform a tick check. Ticks can bite you anywhere on your body but prefer warmer places such as armpits, behind the knees, around the ears and in the hair.

If a tick does happen to bite you, don’t panic. You can remove the tick by following these steps:

- Use clean tweezers to grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible. Be careful not to squeeze the body of the tick during the removal process.

- While firmly squeezing the tweezers, pull the tick straight up and out.

DO NOT burn the tick or attempt to smother it by covering with alcohol or Vaseline. This may cause the tick to inject its gut contents into you, increasing the chance of infection.

- Once removed, do not crush or flush the tick. Instead, save the tick by placing it on a clean, water-dampened paper towel and in a plastic zip bag. Placing the bagged tick in the refrigerator or freezer will help to preserve it in case you want to show your doctor or have the tick tested.

- Wash the tick bite with soap and water and contact your doctor for instructions on what to do next.

- If you decide to have the tick tested, you can visit the following websites for more instructions: https://cvmdl.uconn.edu/tick-testing/how-to-submit/ and https://cvmdl.uconn.edu/tick-testing/options/

Prevention Recommendations: Animal Health

In addition to keeping humans healthy, it is also important to consider preventative measures for pets, such as dogs and cats, as well as horses and other animals kept for pleasure or production.

Domestic animals can be susceptible to tick-borne illnesses, including Lyme disease, ehrlichiosis, and anaplasmosis. Animals that have frequent access to the outdoors, like dogs, horses and livestock, may be more vulnerable due to their close interaction with tick habitats (Figure 6).

Small animal veterinarians may recommend a Lyme vaccine for dogs as well as preventative tick medication for your pets. It is important to administer this medication yearround, as New England winters may no longer sustain the necessary cold temperatures to keep ticks dormant in the environment.

Preventative tick medications vary for different animal species; consult your veterinarian to determine which are best for your pets. For livestock and horses, fly control products containing permethrin may be used responsibly under the direction of your veterinarian to minimize susceptibility to ticks.

Avoid walking or exercising your pet in tick-prevalent areas, such as piles of undisturbed leaves, brush, or tall grass. Take care in urban parks and greenspaces, as well. Check your animals frequently for ticks, especially after hiking or exercising them outside. Complete tick-checks right before you head back inside so that you don’t bring ticks into your barn or home. Livestock should also be checked for ticks during regular management practices, such as feeding, deworming, and tagging.

If you do notice a tick, securely restrain your animal and use tweezers to remove the insect. For ticks that are actively biting an animal rather than crawling on their skin or fur, be sure grab the head of the tick with the tweezers without squeezing the tick’s body.

Wash the space after with soap and water or with rubbing alcohol ,and monitor the animal for visible reactions, such as redness and swelling at the bite site or fever. Signs of a tick-borne illness should be reported to your veterinarian, even if you have not noticed a tick biting your animal. Joint pain and corresponding mobility issues, for example, may be related to tick-borne illness. Other signs may include: lack of appetite, fever, lethargy, weight loss, milk reduction, and kidney disease.

Prevention Recommendations: Plant and Environmental Health

Responsibly managing the natural environment can help to reduce the presence of ticks. If you own a property with a lawn, mow your yard frequently in the summer to prevent the grass from growing taller than three inches. Avoid taking off more than 1/3 of the length of the grass blade at a time to minimize stress on the plant.

To reduce viable habitat further, regularly remove brush as well as leaves after a storm and during the fall season, including around the outside perimeter of the lawn if forested areas are present.

If you keep livestock, mitigate their risk by mowing fence lines, minimizing brush and shrubs in pastures, and avoid grazing wooded pastures during seasons when ticks are most active. New paddocks should be constructed away from the edges of woodland areas whenever possible (Figure 7).

Invasive plants are species that are not native to an environment and that are prone to overtaking an area because of their ability to outcompete native species for resources, such as space and sunlight (Invasive Species | Integrated Pest Management). In addition to being a threat to natural ecosystems, certain invasive plant species can support the presence of ticks.

Remove invasive plant species like garlic mustard (Figure 8) when possible and avoid purchasing invasive plant for your landscape, such as Japanese barberry (Figure 9). Instead, consider creating a landscape composed of native plant species. Using substrate buffers (i.e., mulch, gravel) and native deer-resistant plants at the intersection of lawns and forested areas may also discourage the entry of ticks and their wildlife hosts. Orient leisure and recreational areas away from the tree lines and on substrate like crush stone or mulch; ticks do not want to dry out and will likely avoid the area.

Conclusion

Preventing tick-borne illnesses requires a coordinated approach including human, animal, plant, and environmental health. Consider how you can take action to mitigate the risk of ticks in your life.

Resources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, September 24). How Lyme Disease Spreads. https://www.cdc.gov/lyme/causes/index.html#:~:text=In%20general%2C%20infected%20ticks%20must,areas%20within%20Pacific%20Coast%20states.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, August 28). Preventing Tick Bites. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/prevention/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, May 15). Preventing Ticks on Pets. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/prevention/preventing-ticks-on-pets.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, October 11). Tick Lifecycles. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/about/tick-lifecycles.htmlhttps://www.cdc.gov/ticks/about/tick-lifecycles.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, June 11). What to Do After a Tick Bite. https://www.cdc.gov/ticks/after-a-tick-bite/index.html

Cornell Feline Health Center. (n.d.). Ticks and Your Cat. Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. https://www.vet.cornell.edu/departments-centers-and-institutes/cornell-feline-health-center/health-information/feline-health-topics/ticks-and-your-cat

Gregory, N., Fernandez, M.P., & Diuk-Wasser, M. (2022). Risk of tick-borne pathogen spillover into urban yards in New York City. Parasites Vectors, 15, Article 288(2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-022-05416-2

Invasive Species Advisory Committee. (2019, May 3). The Interface Between Invasive Species and the Increased Incidence of Tick-borne Diseases, and the Implications for Federal Land Managers. U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.doi.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/tick-borne_disease_white_paper.pdf

Jackson, E., Johnson-Walker, Y., Steckler, T., Evans, C., Tuten, H., Stone, C., San Myint., M., & Phillips., V. (2022). Ticked Off Plants: Exploring the Relationship Between Ticks and Invasive Plant Species. University of Illionois College of Veterinary Medicine. https://uofi.app.box.com/s/jlamzhkt9vo47amnyadrirl0bfctmadd

Little, S. E. (n.d.). Vet Tips. University of Rhode Island Tick Encounter. https://web.uri.edu/tickencounter/prevention/protect-your-pets/vet-tips/

Maine Center for Disease Control & Prevention Division of Disease Surveillance. (n.d.). Ticks & Pets. Maine Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/infectious-disease/epi/vector-borne/lyme/ticks-and-pets.shtml

Maine Center for Disease Control & Prevention Division of Disease Surveillance. (n.d.). Tick Prevention and Property Management. Maine Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.maine.gov/dhhs/mecdc/infectious-disease/epi/vector-borne/lyme/tick-prevention-and-property-management.shtml#:~:text=Remove%20leaf%20litter%20and%20brush,difficult%20for%20ticks%20to%20survive.

Machtinger, E., & Springer, H. R. (2019, October 30). Protecting Livestock Against Ticks in Pennsylvania. PennState Extension. https://extension.psu.edu/protecting-livestock-against-ticks-in-pennsylvania

New York State Department of Health. (2023, July). Powassan (POW) Virus Disease Fact Sheet. https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/communicable/powassan/fact_sheet.htm

Slattery, R., & Fritz, M. (2021, June 29). Controlling Flies and Ticks in Your Livestock. University of Maryland Extension. https://extension.umd.edu/resource/controlling-flies-and-ticks-your-livestock/

Stafford, K. C., III. (2014). Managing Exposure to Ticks on Your Property. The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/caes/documents/publications/fact_sheets/entomology/tickcontrolfspdf.pdf?rev=39ddf3261eea4f0e9f0215d09b834dfd&hash=D562BC0854BC63D5A192177A2A6E31FD

Texas A&M University School of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences. (2024, July 11). Keeping Pets Safe from the Threat of Ticks. Texas A&M Today. https://today.tamu.edu/2024/07/11/keeping-pets-safe-from-the-threat-of-ticks/

Vermont Agency of Natural Resources. (n.d.). Ticks and Shoreline Vegetation: Minimize Contact with Ticks While Protecting Water Quality. Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation.https://dec.vermont.gov/sites/dec/files/wsm/lakes/Lakewise/docs/lp_TicksAndShorelandVegetation.pdf

Vogt, N. A. (2024, September). Lyme Borreliosis in Animals. Merck Veterinary Manual. https://www.merckvetmanual.com/infectious-diseases/lyme-borreliosis/lyme-borreliosis-in-animals

Wallace, V., & Siegel-Miles, A. (2016, August). Eco-Friendly Lawns. UConn Extension. https://healthyhomes.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1344/2016/09/11-1-16-HHEco-FriendlyLawns_vw1.pdf

Wilson, J. (2023). Tick Diseases in Horses. University of Minnesota Extension. https://extension.umn.edu/horse-health/tick-diseases-horses

The information in this document is for educational purposes only. The recommendations contained are based on the best available knowledge at the time of publication. Any reference to commercial products, trade or brand names is for information only, and no endorsement or approval is intended. UConn Extension does not guarantee or warrant the standard of any product referenced or imply approval of the product to the exclusion of others which also may be available. The University of Connecticut, UConn Extension, College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources is an equal opportunity program provider and employer.