What is One Health?

Author: Sara Tomis

sara.tomis@uconn.edu

Reviewers: Elsio A. Wunder Jr., UConn Department of Pathobiology; Stacey Stearns, UConn Extension

Publication EXT102 | February 2025

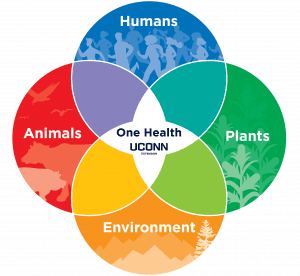

One Health is a collaborative, integrative approach that recognizes the interconnectedness between humans, animals, plants, and the environment. Living beings are closely connected to their natural surroundings. Actions in one area can have positive or negative effects on the health of other species as well as the environment. Concurrently, interactions with animals, plants, and the environment influence our lives and wellbeing.

Recognizing the interconnectedness of human, animal, and environmental systems can help us promote healthier communities and ecosystems, sustainable use of resources, and a more resilient world. Therefore, those who utilize One Health seek to apply a systems perspective to encourage positive change.

This fact sheet is for residents, business owners, municipalities, agricultural producers, and other community members interested in learning how the One Health approach can optimize collective health.

Why is One Health important?

While human beings have always interacted with animals, plants, and the environment, rapid growth in the global human population has intensified interactions with the natural world. Urbanization, for example, has resulted in environmental degradation, and changes to the human-animal interface. Increasing food demands fuel the globalization of agricultural commerce. This global traffic has encouraged the movement of animal and plant species and disease-causing pathogens across continents.

Changes to the climate, accelerated by the reliance on fossil fuels and other non-renewable energy sources, have manifested as extreme weather events, and increased pest and disease pressures. Applying a framework that considers the complexity of a whole system, while emphasizing collaboration, aids in successfully and equitably addressing modern health challenges.

What topics are included in the One Health Framework?

While One Health integrates all aspects of health and wellbeing, priority areas may include zoonotic disease transmission (such as rabies, highly pathogenic avian influenza, and Lyme disease), mental health, water and air quality, food security and safety, biodiversity, and antibiotic resistance.

Positive relationships between species and environment, such as the bond between humans, animals, plants, and nature, are also included in this framework. When applying the One Health approach, the collective health of all components (humans, animals, plants, and the environment) is considered.

Who uses the One Health Framework?

One Health is a global, interdisciplinary approach; many different industries, scientific fields, and organizations are engaged in One Health efforts. In fact, collaboration between disciplines can help to improve understanding and aid in working together towards a more sustainable future.

For example, agricultural producers, water and soil scientists, veterinarians, processing facilities, and food safety professionals may work together to minimize food-borne disease outbreaks and antibiotic resistance.

At UConn, the College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources (CAHNR) is leading the way for One Health within teaching, research, and extension. CAHNR exemplifies the nexus between human, animal, plant, and environmental sciences. Students enrolled at UConn have access to One Health curricula through CAHNR and research conducted by CAHNR scientists teaches us how to optimize health in our communities and world. UConn Extension connects the One Health research of the university to those who will put it into practice.

Providing services to those in the animal industry, the Connecticut Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory (CVMDL) is on the front lines of zoonotic disease surveillance. CAHNR is committed to advancing One Health for the good of all species and the environment.

How can you engage with One Health?

Anyone can engage with One Health and use its framework to improve individual and community health and well-being. The following are recommended practices for residents, businesses, agriculturalists, and community leaders:

- Educate yourself about One Health by reading credible articles and fact sheets, participating in workshops and events, and talking with professionals.

- Reflect on how you interact with animals, plants, the environment, and other people through your personal and professional activities. Identify areas of improvement for decreasing potential disease transmission or negative environmental impacts.

- Consider how to take action to protect personal health during natural disasters, disease outbreaks, and other animal, plant, and environmental challenges. Prevention is an important first step and can help decrease potential damage.

- Identify ways to promote positive change by working to conserve resources, promoting biodiversity, safely interacting with livestock and pets, and more.

- Volunteer for initiatives that apply the approach. Teach others about One Health to enhance the collective health of your community.

Additional resources and engagement opportunities are available at onehealth.cahnr.uconn.edu and listed below.

Resources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, April 16). Antimicrobial Resistance in People and Animals. https://www.cdc.gov/one-health/php/stories/ar-in-people-and-animals.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, October 10). Working Together for One Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/one-health/php/stories/working-together-for-one-health.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, October 30). About One Health. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/one-health/about/index.html

Forghani, F., Sreenivasa, M. Y., & Jeon, B. (2023). Editorial: One Health Approach To Improve Food Safety. Frontiers in Microbiology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2023.1269425

One Health High-Level Expert Panel (OHHLEP), Adisasmito, W. B., Almuhairi, S., Behravesh, C. B., Bilivogui, P., Bukachi, S. A., Casas, N., Cediel Becerra, N., Charron, D. F., Chaudhary, A., Ciacci Zanella, J. R., Cunningham, A. A., Dar, O., Debnath, N., Dungu, B., Farag, E., Gao, G. F., Hayman, D. T. S., Khaitsa, M., Koopmans, M. P. G., Machalaba, C., Mackenzie, J. S., Markotter, W., Mettenleiter, T. C., Morand, S., Smolenskiy, V., Zhou, L. (2022). One Health: A new definition for a sustainable and healthy future. PLoS pathogens, 18(6), e1010537. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1010537

Stearns, S. (2024, April 23). CAHNR One Health Initiatives Addressing Human, Animal, and Environmental Issues. UConn Today. https://today.uconn.edu/2024/04/cahnr-one-health-initiatives-addressing-human-animal-and-environmental-issues/

Torres, A. G. (2017). Escherichia coli diseases in Latin America—a ‘One Health’ multidisciplinary approach. Pathogens and Disease, 75(2), Article ftx012. https://doi.org/10.1093/femspd/ftx012

Willis, B. (2022, July 18). A One Health Approach for Better Health Solutions. The University of Arizona Health Sciences. https://healthsciences.arizona.edu/news/stories/one-health-approach-better-health-solutions

World Health Organization. (2023, October 23). One Health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/one-health

The information in this document is for educational purposes only. The recommendations contained are based on the best available knowledge at the time of publication. Any reference to commercial products, trade or brand names is for information only, and no endorsement or approval is intended. UConn Extension does not guarantee or warrant the standard of any product referenced or imply approval of the product to the exclusion of others which also may be available. The University of Connecticut, UConn Extension, College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources is an equal opportunity program provider and employer.