Invasive Plant Factsheet: Hydrilla, water thyme

Hydrilla verticillata

Author: Lauren Kurtz, Alyssa Siegel-Miles, and Victoria Wallace

lauren.kurtz@uconn.edu

Reviewer: Summer Stebbins, CASE

Publication #EXT061 | March 2024

Many infestations of hydrilla begin near boat launches. Even plant fragments can survive moist conditions for several days. This fact sheet should be of interest to those boating throughout the state, well as natural resource managers. Boaters are asked to avoid boating through beds of aquatic vegetation, and before leaving a boat launch, to clean, drain, and dry boats and trailers before traveling home or to another body of water.

Habitat

Hydrilla is highly adaptable to diverse environments. It can grow in deep or shallow water; it occurs in lakes, ponds, streams, marshes, and rivers. It can tolerate fresh and brackish water (up to seven percent salinity). It can grow in low or high light conditions and tolerates a wide range of nutrient availability and pH.

Identifying Features

- Overview: Hydrilla, also called water thyme, is a submersed aquatic plant that typically grows rooted in the sediment, but can grow as a free-floating plant when fragmented. Hydrilla forms dense mats of vegetation that quickly outcompete native species for habitat, as well as make navigating waterways difficult for boats and aquatic species. Known as one of the most noxious aquatic invasive plants, it grows extremely fast and is adaptable to many environments.

- Leaves: Whorled around the stem in groups of five (occasionally in groups of four to eight). Bright green, lance-shaped, 0.2-0.4 cm wide and 0.6-2 cm long, with serrated margins

- Stems: Slender stems reach from the sediment to the surface of the waterbody and can grow over seven meters. At the water’s surface, stems are highly branched, forming dense mats of vegetation

Stems produce reproductive structures called turions (vegetative buds that can grow into new plants)

- Flowers: Hydrilla plants may be monecious (male and female plant parts on single plant) or dioecious (plant is either female or male). In Connecticut, there is a monecious genotype; the Connecticut River Strain of hydrilla is not yet identified as being either monecious or dioecious.

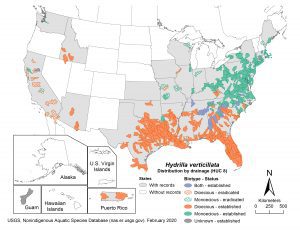

Hydrilla verticillata distribution by biotype and population in the United States. USGS. Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database.

Flowers are small (0.3 cm across), translucent to reddish white, attached to the plant on long stalks, and float on the surface.

- Seed/fruit: Hydrilla does produce seeds, but is mainly spread by vegetative propagules, including tubers, turions, and stem fragments.

- Roots: Hydrilla roots in the sediment, but can also grow as a free-floating plant when fragmented. Roots produce reproductive structures called tubers.

- Reproduction/spread: Largely clonal methods of reproduction and spread through axillary turions on the stem, subterranean tubers, and stem fragments. Tubers can remain dormant in sediment for years before sprouting. Boats, boat trailers, water currents, and waterfowl are the primary sources of spread.

Control

Mechanical and chemical controls are costly and only moderately effective. Prevention is the most effective method of controlling hydrilla, as the plant is easily spread by stem fragments attached to boats, boat trailers, or in water wells of boats. Control methods are most effective with smaller populations, while large infestations are extremely difficult and costly to control.

Prevention: Many infestations begin near boat launches. Plant fragments can survive moist conditions for several days. If possible, avoid boating through beds of aquatic vegetation. Before leaving a boat launch, clean, drain, and dry boats and trailers before traveling to another waterbody or home. Carefully inspecting boats and trailers and removing any plant fragments is essential to reducing the spread of hydrilla. Eliminate all water from your vessel before you leave the area. Dry equipment for an adequate amount of time before entering new waters (preferably five days). Open airlocks after use and allow to dry thoroughly. Dispose of hydrilla in a specified plant disposal station on site, if available.

Mechanical: Physical barriers, such as benthic barriers/mats, (large blankets placed on sediment to block sunlight and prevent vegetation growth) can be effective, especially when used near boat launches or at marinas. Mechanical removal with mowers, suction, or dredging can be effective, however, care must be taken to reduce plant fragmentation and capture buried tubers. Repeated treatments are required. Water drawdown of an area can be done on a small scale, but effectiveness is limited if tubers are not removed from the sediment.

Chemical: Instructions defined on the label are the law and must be adhered to when using all chemical products.

The recommendations below may require a licensed professional applicator and permits from a regulating agency.

When timed correctly, herbicides can be used to control hydrilla populations. They are unlikely to completely eradicate infestations, as repeated treatments are necessary.

Permits for using aquatic herbicides can be difficult to obtain, especially for flowing bodies of water, areas with native species of concern/state listed species, and/or drinking water sources. Diquat dibromide, Fluridone, Endothall and Florpyrauxifen-benzyl are commonly used to control hydrilla. Be aware that some herbicides used for hydrilla management are non-selective and may negatively impact native plant populations.

Biological: The use of biological controls for hydrilla is still in its infancy, with mixed results. Triploid sterile grass carp have been introduced into contained waterbodies to eat hydrilla, but the carp also consume native plant species. The use of these fish requires special permitting for introduction to waterbodies and are only an option where migration out of a pond can be prevented.

A leaf-mining fly (Hydrellia pakistanae) and the larvae of a weevil (Bagous affinis) have been tested as biological controls of hydrilla with limited or inconclusive results to date.

Distribution

Hydrilla is native to tropical Asia; it can now be found on all continents except Antarctica. It was first identified in the United States in 1960 in Florida, likely the result of an escaped or discarded aquarium plant. Hydrilla was first identified in Mystic, Connecticut in 1989 and now inhabits other Connecticut waterbodies (Fig 4). A distinct genotype of hydrilla was found in the Connecticut River in 2016 near Glastonbury. This strain is more robust, has more leaves per whorl, produces more turions, but does not produce tubers. This Connecticut River strain now inhabits six waterbodies outside of the Connecticut River, in both Connecticut and Massachusetts.

Other facts and background: Hydrilla infestations promote the growth of cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae. The algae produces a neurotoxin, which attacks the nervous system of waterfowl when they consume hydrilla serving as a host plant to the bacteria. Although not seen in Connecticut, this toxin has been linked to the death of waterfowl and eagles in the southern United States.

References

Capers RS, Bugbee GJ, Selsky R, White JC. (2005). Invasive Aquatic Plants of Connecticut. ConnecticutAgricultural Experiment Station. https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/CAES/OAIS/Plant-Information/AquaticsGuidepdf.pdf

Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station. (2012). Hydrilla verticillata. Invasive Aquatic and Wetland Plant Identification Guide. https://cipwg.media.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/244/2015/03/2012_caes_aquaticguide_hydrilla.pdf

Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. (n.d.). Aquatic Invasive Species.

https://portal.ct.gov/DEEP/Fishing/General-Information/Aquatic-Invasive-Species

Connecticut River Conservancy. (n.d.) About Hydrilla. https://www.ctriver.org/get-involved/stopping-an-invasive-species-water-chestnut-2/hyrilla-in-the-ct-river-watershed/

Cornell Cooperative Extension of Tompkins County. (n.d.). Hydrilla Biological Controls. https://ccetompkins.org/environment/aquatic-invasives/hydrilla/management-options/biological-controls

National Invasive Species Information Center. (n.d.). Hydrilla.

https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/aquatic/plants/hydrilla

New York Invasive Species (IS) Information. (2019). Hydrilla.

https://nyis.info/invasive_species/hydrilla/#Introduction

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. (n.d.). Connecticut River Hydrilla.

https://www.nae.usace.army.mil/Missions/Projects-Topics/Connecticut-River-Hydrilla/

Figures

Fig 1. Illustration of hydrilla morphology. IFAS, Center for Aquatic Plants. University of Florida.

Fig 2. Close up of hydrilla forming a mat of vegetation. Leslie J. Mehrhoff, University of Connecticut,

Bugwood.org.

Fig 3. Waterbody infested with hydrilla. Office of Aquatic Invasive Species. Connecticut Agricultural

Experiment Station.

Fig 4. Hydrilla verticillata distribution by biotype and population in the United States. USGS.

Nonindigenous Aquatic Species Database.