Fireblight & Mitigating Resistant Populations

Author: Evan Lentz, Assistant Extension Educator, Fruit Production and IPM

Publication # EXT004 | June 2023

Reviewers: Shuresh Ghimire, Assistant Extension Educator, UConn Extension and Mary Concklin, Extension Educator Emeritus, UConn Extension

Introduction to Fireblight

After a few weeks of visiting with fruit growers in the state, it's clear that Fireblight remains one of the top concerns for the fruit industry. This disease, caused by the bacterium Erwinia amylovora, is both highly destructive and infectious, making informed disease management efforts a top priority. As the growing season ramps up, it's important to revisit this disease's existing management considerations while incorporating new research from our regional IPM team members including the discovery of Streptomycin-resistant Fireblight.

Disease Cycle, Signs, and Symptoms

Erwinia amylovora overwinters in cankers formed on the trunks and branches of infected trees (Figure 1). Plants belonging to the Rosaceae (Rose) family are susceptible. This includes apple (Malus), pear (Pyrus), hawthorn (Crataegus), serviceberry (Amelanchier), quince (Cydonia), chokeberry (Aronia), mountain ash (Sorbus), and many others. These cankers excrete a tan bacterial ooze, which serves as inoculum for both initial and re-infection and often can go unnoticed until other symptoms present later in the season.

Initial infections rely on entry through wounds or natural openings such as flowers during bloom. This disease is easily spread - vectored by wind, rain, insects, or tools and equipment used in orchard management.

The most readily identifiable symptom is the characteristic "shepherd's crook", where shoots tips die and begin to curl back on themselves, appearing burnt (Figure 2). Flowers also show symptoms of infection, starting with a water-soaked appearance and eventually shriveling up and turning brown or black. Infected fruits follow this same pattern. If left untreated, this disease will kill the entire tree.

How it is Currently Managed?

Resistant/Tolerant Cultivars - Some resistant cultivars are available such as Keiffer and Seckel pear, early Fuji, Honeycrisp and Zestar apples.

Although not an option for existing orchards, some may want to consider this option when establishing new blocks of trees.

Monitoring - This is perhaps the most important part of your management plan and your most effective tool in preventing blossom infections. Two disease forecasting models, MaryBlyt and CougarBlight, are available to inform you spray decisions. The NEWA system uses the CougarBlight model and can be accessed at: https://newa.cornell.edu/fire-blight

Chemical Control:

Copper - Copper is an early season material that kills bacteria on the plants surface. This is an effective way to reduce the overall population of Erwinia amylovora in an orchard for 2-3 weeks, depending on weather conditions.

Taken from the New England Tree Fruit Management Guide:

"There are many copper formulations. Apply a minimum of 2 lb. of metallic copper per acre. If in doubt about how much metallic copper a product contains, use the high label rate recommended at silver to green tip. Copper may be used with oil (1 qt./100 gal.), which can act as a spreader/sticker for the copper. Because copper sprays are meant to suppress the population of E. amylovora in an entire orchard, spray the whole orchard, not just the most susceptible cultivars or places where fire blight has occurred in the past."

Antibiotics - Antibiotics should be applied during bloom when forecasting systems signal a high risk for infection. Antibiotics are also to be used after a trauma event, such as hail.

Cultural Management:

Pruning - Prune out infected branches. Cuts should be made at least 8 inches below any visible damage. Prune during dry weather only so you don't move the bacteria.

Sanitation - Pruning tools need to be disinfected between each pruning cut during the growing season so that the infection is not spread from cut to cut. A 70% alcohol or 10% bleach solution will provide an acceptable level of sanitation.

Fertilization - Avoid overfertilization. Large amounts of nitrogen can lead to excessive vegetative growth and succulent green tissue, increasing the plant's susceptibility to infection.

Streptomycin-Resistant Fireblight

Numerous samples from around the Northeast United States, specifically in western New York state, have tested positive for resistance to Streptomycin, one of the few materials that are effective at controlling Fireblight. This is due to 50+ years of sustained use in orchards. Figure 3 shows the locations in New York where Strep-resistant Fireblight has been confirmed over the past three years (2020-2022).

From Dr. Quan Zeng at CAES:

"48 samples were collected in 2022 from orchards in CT, NH, and NY (Hudson valley). The fire blight pathogen Erwinia amylovora was isolated and tested on media supplemented with streptomycin at the concentration of 100ug/ml. All strains were tested negative for streptomycin resistance in 2022. We will continue to test in the coming years. If you have samples that you wish to be tested, please send your samples (fresh samples with ooze preferred) to Dr. Quan Zeng, Plant Pathology JW106, 123 Huntington Street, New Haven, CT. If you would like a farm visit, please contact Dr. Quan Zeng at 832-671-3499."

What is Pest Resistance?

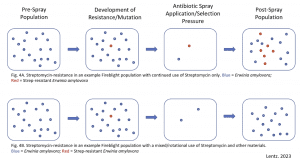

Pest resistances often arise when a mutation that confers some level of resistance occurs to a single individual in a population. Repeated use of a single material, such as Streptomycin, works to diminish the individuals in the population without the mutation while allowing the individual(s) with the mutation to grow and multiply, unchecked. This is what is called a selection pressure. Over time, more and more individuals in the population will have the mutation, leading to a resistant population (See Figure 4A).

However, these mutations are very rare, and it takes time for the mutations to build up in a population. Utilizing more than one material, usually with a different mode-of-action, will ensure that individuals with resistance to the first material are reduced and the proliferation of the mutation remains minimal (See Figure 4B). This is how selection pressure can be effectively reduced and why it is suggested to rotate or mix materials often whether the pest is a weed, insect, or bacterium.

How can we manage Strep-resistant Fireblight?

Recommendations from Dr. Kerik Cox from Cornell and Dr. Quan Zeng from the Connecticut agricultural Experiment Station.

Pre-season:

Prune out the cankers.

Dilute delayed-dormant Fixed Copper application at silvertip (15% MCE, metallic copper equivalent). Ensure proper coverage. Calibrate your sprayers.

Tight Cluster - Pink:

Early Prohexadione Ca (PhCa) - 6oz/100 gal OR 2oz/100 gal + 1oz/100 gal ASM (Actigard)

Start defense inducers at Pink

Bloom:

Use NEWA model or consultant/Extension for Fireblight infection periods.

Models may overpredict infection risk. Shouldn't need more than 3 applications; really only 1 well-timed application.

EIP Thresholds & Bactericides Selection

-

- EIP > 100: Streptomycin or Kasugamycin

- EIP 40-70: Oxytetracycline or a biological

If you do not have Strep-resistant Fireblight:

-

- It is still important to protect yourself against developing resistance.

- Rotate antibiotics at Bloom:

- 1) Mix Streptomycin and Oxytetracycline at the full rate

- 2) Alternate with Kasugamycin

- Apply on cloudy days or in the evening

- 3) Alternate with Oxytetracycline (unless you used it in the mix), copper (if it's safe to do so), or biologicals (Blossom Protect, etc. [slight chance of russeting under humid conditions])

If you do have Strep-resistant Fireblight:

- Rotate materials at Bloom:

- 1) Kasugamycin (Kasumin 2L) at 64 fl oz/A in 100 gallons

- 2) Blossom Protect ( 1.25 lbs/A + 8.75 Buffer Protect) applied twice at 70-90% Bloom (slight change of russeting under humid conditions)

- 3) Oxytetracycline or other biopesticide/copper at the highest rate

- Might need to make more applications. Use NEWA forecasts, apply prior to EIP of 60-100 during wet weather at bloom.

- Make applications at night if possible.

Note: Blossom Protect has a slight chance of causing russeting under humid conditions. Blossom Protect is also sensitive to scab fungicides therefore cannot be used together with such materials. Application of fungicides at petal fall may eliminate Blossom Protect yeast and reduce russeting.

Post-Bloom, Petal Fall:

Prohexadione Ca - Apply 6 oz/100 gal (or 2 oz/100 + 1 oz/100 gal ASM; Actigard) at petal fall and 10-14 days later

Post-Bloom & Summer:

Copper (protectant and organic only) - can cause fruit russet. Only use if you're concerned about losing trees to the disease. Apply on a sunny, dry day. This will only protect against the bacteria already on the plant's surface. As the plant grows, new tissue will not be protected. Repeat applications at a low rate will be needed until terminal bud set.

Pruning - remove strikes/blighted branches promptly on a cool, dry day. Prune into last season's growth (at least 12" into healthy tissue. For younger trees, if 12" is into the main scaffold of the tree, remove and replant.

Rescue Program - apply PhCa 6-12 oz/100 gal, wait 5 days, and prune every two weeks until terminal bud set.

We are hopeful that with these strategies further development of antibiotic resistance in Fireblight populations can be mitigated. For more information, please visit the sites below or contact your local Extension or CAES offices.

Additional Resources

https://netreefruit.org/apples/diseases/fire-blight

https://portal.ct.gov/CAES/Fact-Sheets/Plant-Pathology/Fire-Blight

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-hi9guUp0Ho

https://ipm.ucanr.edu/PMG/PESTNOTES/pn7414.html

Support

Evan Lentz - CT Fruit and IPM Specialist - evan.lentz@uconn.edu

Dr. Quan Zeng - CT Fireblight Expert - Quan.Zeng@ct.gov

References

Cooley, D. et al. 2020. New England tree fruit management guide. UMass Extension. https://netreefruit.org/

Cox, K.D. 2023. Fire blight fruit school: new research from our national team [PowerPoint slides]. Cornell.

DuPont, T. 2023. Fire blight of apple and pear. WSU Extension. https://treefruit.wsu.edu/

Johnson, K.B. 2000. Fire blight of apple and pear. The Plant Health Instructor. DOI: 10.1094/PHI-I-2000-0726-01

Smith, S.A. 2017. Pest fact sheet 32: fire blight. UNH Extension. https://extension.unh.edu/